︎ ︎︎

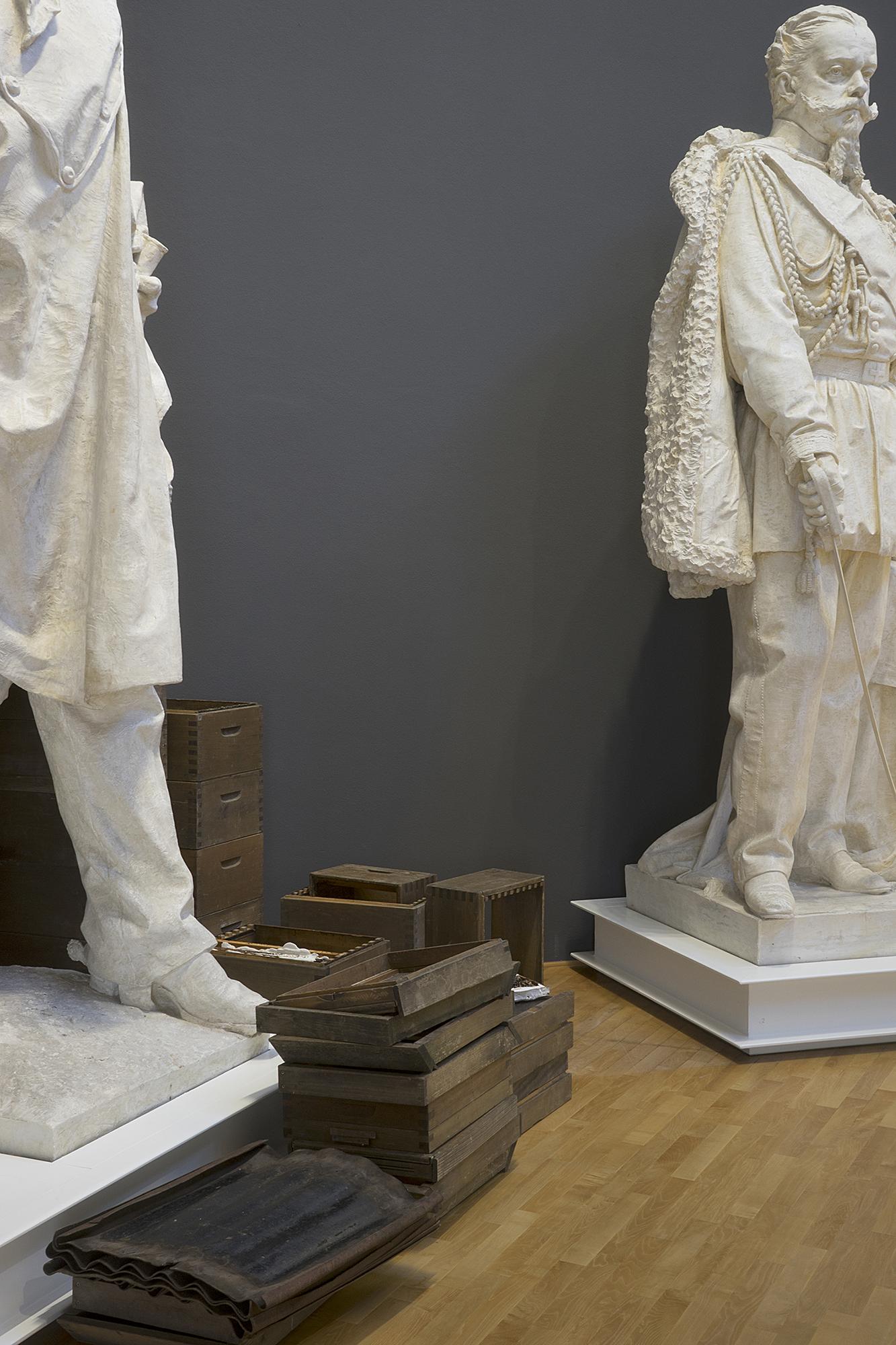

Mal d’archive (Archive Fever), 2012 - 2016

Beehives, plaster, beeswax

Dimensions variable

Exhibition view: La classe sterile, Museo Vincenzo Vela, Ligornetto, 2016

In this sense, what would be the best form for a beehive? And what would be the best form for an archive? Indeed, honeybees themselves have a peculiar sense of order and space. But, really, what would be the best form to house the history and memory of socialized lives?

Beehives, plaster, beeswax

Dimensions variable

Exhibition view: La classe sterile, Museo Vincenzo Vela, Ligornetto, 2016

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the beehive emerged as a conceptual tool to reimagine political systems and economic theories. At the same time, a new apiarian system changed radically— and systematically since Lorenzo Langstroth’s hive patented in 1852 —honeybees’ “domestic” environment. It did not just improve bee exploitation favoring monoculture through carpet pollination. It reorganized the entire superorganism, a “process of ‘domestic’ rationalization.”

In this sense, what would be the best form for a beehive? And what would be the best form for an archive? Indeed, honeybees themselves have a peculiar sense of order and space. But, really, what would be the best form to house the history and memory of socialized lives?